Written records of cancer date back to the Ancient Egyptians, who believed it was an ailment sent by the gods. Since then, humans have made many discoveries about cancer, its causes, and different treatments to fight it, but none are 100% effective. Recently, a team of researchers at Columbia University designed a new method to fight cancerous tumors using a combination of bacteria and viruses.

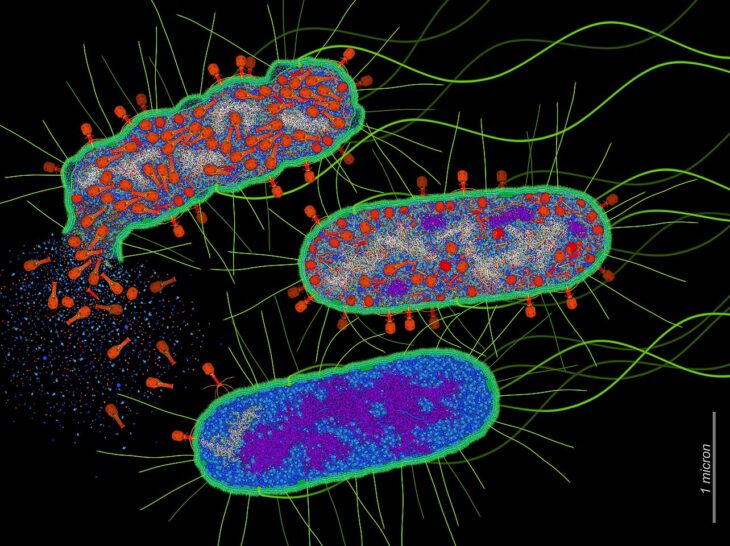

The team developed this new strategy by infecting cells of the bacterium Salmonella typhimurium with the virus Senecavirus A. They explained that when tumor cells absorb these bacteria, they should become infected with the virus, replicate it within themselves, and then die, spreading it to other cells. If this process is successful, the virus should destroy the entire tumor. The team referred to this method as Coordinated Activity of Prokaryote and Picornavirus for Safe Intracellular Delivery, or CAPPSID.

To begin their research, the team tested whether S. typhimurium is a valid host for Senecavirus A. They infected a small number of these bacteria with an altered version of the virus that produced fluorescent RNA, and added a solution that helps the virus enter the bacteria. Then, they used a fluorescence microscope to search for viral RNA within the bacterial cells and confirm they were infected. Finally, they added 2 proteins to the infected bacteria to help the viral RNA escape from the bacteria and enter the cancer cells. They added these proteins to help control the virus’s spread before the bacteria died, so it wouldn’t infect any non-cancerous cells.

Once the scientists had successfully modified the bacteria and the virus, they tested the virus’s delivery system on a sample of cervical cancer. They found that the virus’s RNA was able to replicate outside the bacterial cells and inside the cancerous cells. They also documented the presence of more newly-synthesized RNA strands in the tumor cells, confirming that their CAPPSID method successfully delivered the virus and that the virus was replicating.

Then, the team tested whether CAPPSID affected a specific type of cancer cells called small-cell lung cancer, or SCLC They again tracked fluorescent viral RNA in SCLC cells to measure how quickly the virus spread after infection. They found that the virus continued to spread at the same speed for up to 24 hours after the initial infection, indicating that it could spread through cancer-affected areas without losing momentum.

Next, the researchers tested their CAPPSID method on 2 groups of 5 mice. They grafted SCLC tumors onto both sides of the mice’s backs. They engineered Senecavirus A to produce a bioluminescent enzyme so they could track its spread, and injected the CAPPSID bacteria into the cancer on the right side of the mice. They found that the right side tumors glowed 2 days after injection, meaning the virus was active. Four days later, the left side tumors also glowed, indicating that the virus had traveled across the mice’s bodies and infected the cancer without infecting healthy tissue elsewhere.

The researchers treated the mice for 40 days, but within 2 weeks, their tumors had shrunk to an undetectable size. They further monitored the mice for 40 days after the tumors were cleared, and found that the mice had a 100% survival rate with no recurring cancer, major symptoms, or side effects. Through this experiment, the team found that the CAPPSID virus could bypass the immune system because it was encapsulated by the bacteria, meaning the cancer cells couldn’t develop immunity to it.

Finally, the team needed to prevent Senecavirus A from replicating and spreading uncontrollably. They isolated a gene from a tobacco virus that produces an enzyme used to convert vital Senecavirus A proteins into their active, usable form. They engineered this gene into the bacterium Salmonella typhimurium, which allowed it to make this specialized enzyme on its own. They reasoned that this way, the virus couldn’t become active or spread unless the bacteria were also present. The scientists tested this modified CAPPSID method on 2 more groups of 5 mice and found that the virus spread more successfully and was contained within the cancer-affected area.

The researchers claimed that their results could form the basis for new cancer treatments. The disappearing tumors in the mice, the ability of the CAPPSID system to target only tumor regions, and the lack of side effects could mean that human cancer patients could be treated similarly, without radiation or harmful chemicals. However, they also acknowledged a risk that the virus or bacteria could mutate, potentially limiting CAPPSID’s effectiveness and causing unexpected side effects. They suggested that adding more enzymes from the tobacco virus could overcome potential complications by further regulating the virus’s replication, enabling further research into new cancer-fighting therapies.