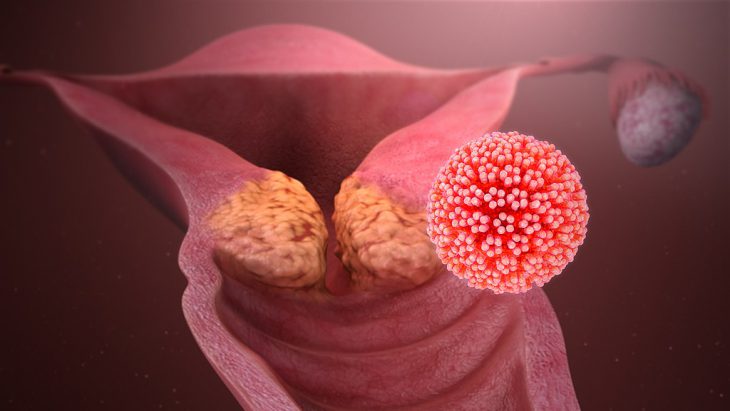

HPV, otherwise known as human papillomavirus, is a family of related viruses that are transmitted sexually. These infections can be dangerous when not monitored and may lead to cancer. Infection with either HPV variant 16 or 18 is known to increase the risk of cervical, vaginal, and vulvar cancers in women along with penile cancer in men.

Ninety-nine percent of cervical cancers are caused by HPV infection. HPV 16 and 18 make cells in the cervix abnormal or precancerous. These cells have not yet progressed to full cancer, and the condition is known as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Scientists want to understand how the virus manages to convert healthy cells to abnormal, precancerous cells.

Researchers at the National Natural Science Foundation of China studied tissue samples from 60 patients who had undergone hysterectomies, a surgery in which the uterus is removed. Next, the researchers used a process that isolates specific cells using a powerful microscope, called laser capture microdissection, to identify normal and precancerous cervical cells in the samples.

Extracting and studying the RNA from a sample tells researchers what genes are turned on. Knowing this, they performed RNA sequencing on the samples to determine which RNAs were most abundant. They found a lot more RNA for a gene that makes a protein called APOBEC3B in the precancerous samples than in the normal cells. They looked up information about the molecule in a public database called The Cancer Genome Atlas to learn more about it, and also measured how much was produced.

Next, the researchers looked for the APOBEC3B protein in normal cervical tissue and in precancerous cervical tissue. To do this, they used a technique that stains APOBEC3B in the tissue sample brown. The darker the stain, the more protein was present. The researchers grouped the samples by how strong the APOBEC3B expression was on a scale of 0 to 3, from no expression (zero) to strongly expressed (three). They saw that the more progressed the cancer was, the more APOBEC3B protein was found. They also found that high levels of APOBEC3B were found more often in patients whose cervical cancer had spread to their lymph nodes.

The researchers’ next question was how APOBEC3B promotes progression from pre-cancer to cancer. By knowing how APOBEC3B causes progression, new drugs can be developed that interfere with the process. Previous research on HPV has shown that the virus makes two proteins to cause cancer. These proteins are called E6 and E7. The researchers observed that the E6 attaches to the DNA that contains the instructions for synthesizing APOBEC3B and turns it on. This means that the amount of APOBEC3B that the cell makes will increase when the E6 protein from HPV is present.

The researchers hypothesized that if E6 proteins bind to the APOBEC3B-making gene, there would be more APOBEC3B in cervical cancer cells with more E6. Using a stain that turns APOBEC3B brown, they detected exactly that. Also, when they removed E6 protein, APOBEC3B levels decreased. Therefore, they concluded E6 regulates the abundance of APOBEC3B.

In the next set of experiments, the researchers demonstrated that when they remove APOBEC3B, this hinders cervical cancer cell growth. They observed this slower growth both in a cell culture dish and when they put the cells without APOBEC3B into mice. Injecting cancer cells into mice is one way that researchers test tumor formation. Knowing how APOBEC3B controls tumor cell growth in mice can be beneficial to humans. They took the tumors from the mice and stained them to check for molecules that cause the cells to divide.

One of these molecules is called cyclin D1. They found that in the cells without APOBEC3B, there was less cyclin D1, showing that far fewer cells were dividing. They concluded that APOBEC3B levels control the levels of cyclin D1. With more cyclin D1, cells are more likely to divide. When the cell division gets out of control, cancer occurs.

Ultimately, the researchers found that E6 is the first step of the domino effect. When it is produced, APOBEC3B goes up, and then so does cyclin D1, resulting in cancer proliferation. This can cause a progression to invasive cancer.

The authors explain that since they only did experiments removing APOBEC3B, it would have been useful to see how the results would be when cells would have too much APOBEC3B. Secondly, another research group found that a related protein, APOBEC3A, was lower in cervical cancer than in normal cells. Because of this, more research is needed. If their findings are confirmed by further research, this will be useful when designing new drugs that interfere with this process.