Life as we know it depends on chemistry. But could reproduction, one of life’s defining features, happen without biology? From bacteria to humans, every organism follows a complex chain of chemical reactions, yet scientists have long wondered if non-living chemistry alone can do the same. Could a system made entirely of non-living chemicals spontaneously grow, reorganize, and multiply?

Sai Krishna Katla, Chenyu Lin, and Juan Perez-Mercader from Harvard University sought to answer this question. They developed the first fully non-biological “artificial cells” that reproduce independently. Their system uses no enzymes, nucleic acids, or lipids. Instead, it’s built from simple molecules that organize into microscopic bubbles, called vesicles, and, under certain conditions, divide to form new sets of vesicles.

The team combined small molecules that don’t mix with water to form larger ones that do, using a method called polymerization-induced self-assembly or PISA. Molecules with one water-loving side and one water-repelling side are known as amphiphiles. Amphiphiles naturally assemble into spherical layers that act as boundaries, similar to biological cell membranes.

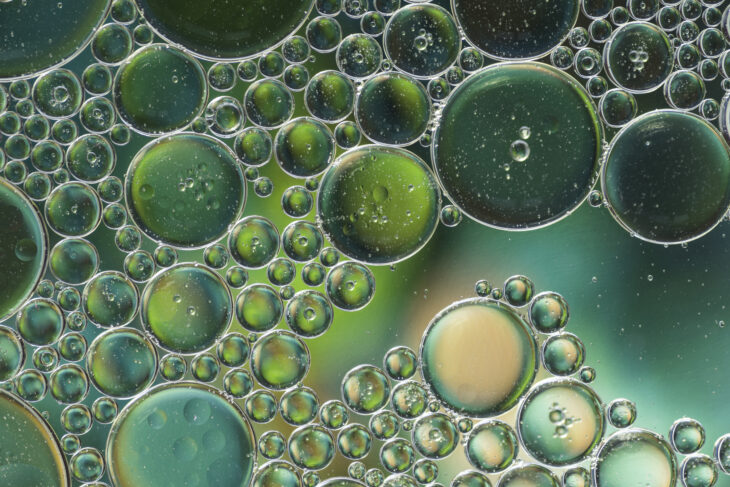

To drive this process, the researchers mixed a few simple ingredients. These included a water-loving material to form the bubble walls, a small, slightly water-repelling regulator molecule to help control the reaction by stopping the growing chains from getting too long, and a light-sensitive compound, called a photocatalyst, to power the process. When they exposed this mixture to green light, it triggered the ingredients, starting a chain reaction that caused the individual ingredients to join into long molecular chains via a process called polymerization. They found that the chains spontaneously formed microscopic vesicles roughly the size of bacteria.

The team watched the vesicles for about 12 hours using a light microscope. They saw that the number of vesicles increased steadily and multiplied faster than ordinary chemical reactions, which usually proceed at a steady pace where products form directly from reactants.

With constant exposure to green light, the “parent” vesicles ejected tiny fragments of partially-formed polymers, which eventually polymerized and self-assembled into new “offspring” vesicles. This cycle of ejection, polymerization, and self-assembly produced new generations of vesicles without any biological machinery. The team described it as a form of self-reproduction, driven purely by chemistry and physics.

To confirm this reproduction cycle, the researchers ran a control experiment. They filtered the mixture through a membrane, separating the formed vesicles from free molecules. Then, using a light microscope, they watched both samples under green light. Only the filtered vesicles produced new generations over time, while the solution with free molecules stayed unchanged. This showed that new vesicles originate from existing ones, rather than forming through random chemical assembly.

The team also noticed that the length of the polymer chains making up the membranes of the newly formed vesicles shared this feature with their predecessors. This happened because the parent vesicles expelled partly formed polymer molecules that still carried active ends, allowing them to keep reacting and form new vesicles nearby. In this way, some structural characteristics of the parent vesicles were chemically passed on to their offspring.

The team also tracked the photocatalyst to see if it was being passed on from the parent vesicles to the offspring fragments. They found that about 94% of new vesicles contained the photocatalyst, demonstrating that it was passed from one generation to the next, via a primitive form of chemical inheritance.

Over time, the researchers saw that the vesicle population followed 3 growth phases, similar to how microbial populations grow. At first, the vesicles formed rapidly, fueled by abundant monomers. Then, the reaction consumed its chemical supply, and they grew more slowly. Once the initial vesicles began releasing fresh monomers into solution, their growth accelerated again. Finally, the growth rate slowed and stabilized after the third phase. As the number of vesicles increased, their average size decreased, as larger parent vesicles expelled smaller offspring, which in time grew and matured.

The researchers concluded that pure chemical reactions involving amphiphiles can trigger cycles of growth and division without any biological involvement. In essence, the polymer vesicles act as chemical analogs of living cells. They use light as an “energy source,” consume monomers as “food,” and “reproduce” when internal buildup forces them to reorganize. The variation in polymer chain length between generations even creates a form of heritable diversity.

The researchers suggested that this discovery could help explain how life might arise from non-living matter. They noted that these non-biochemical self-reproducing systems could explain how early protocells functioned before life evolved. They also proposed that similar chemical systems might exist beyond Earth. Beyond origins of life research, they hope these artificial cells will inspire scientists to create new experimental models to study evolution.