Carbon capture initiatives (CCI) are technologies which filter out CO2 from gases release from burning fuel before it reaches the atmosphere. There is substantial scientific evidence that CO2 released by human activities is causing increases in global average temperature, otherwise known as climate change. For this reason, technology to remove carbon from the atmosphere, called carbon capture, is receiving greater attention from governments and investors around the world.

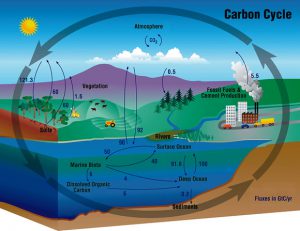

This is the global carbon cycle to show you where all that carbon came from. Source: Wikimedia Commons

There are several existing carbon capture methods that filter out CO2 using heat, pressure, or special filter or absorbing materials (solvent scrubbing). However, all of these techniques are difficult to scale, require lots of energy, and are hard to build into existing systems. Furthermore, most are designed for large-scale combustion and other industrial fumes that produce gases with high CO2 concentrations — above 10%.

Researchers Sahag Voskian and T. Alan Hatton at MIT engineered a revolutionary new carbon-capture technique called ‘electro-swing-absorption’ (ESA), which overcomes many of these existing issues. They created a specialized battery that absorbs CO2 from air as it passes through the device. In addition to their study on this device, they plan to commercialize the process through their startup company, Verdox.

The battery uses some newly engineered materials which make up a cathode (negative end of the battery) and an anode (positive end of the battery). The researchers built these from tiny particles called carbon nanotubes. They coated the anode with an iron-based chemical called ferrocene and the cathode with a large organic molecule called polyanthraquinone.

They sandwiched these together into layers with channels so that gas can flow between them. The researchers measured the pressure of a stream of air they passed through the device during charging and discharging to test how well the battery absorbs CO2. Experiments were repeated for a variety of CO2 concentrations to mimic exhaust gas from combustion and different types of ambient air to determine how well the filter worked.

On charging, they found CO2 molecules bind to the cathode surfaces through a chemical process known as reduction. In reduction, the CO2 molecule gains two extra electrons. After that, CO2 attaches itself to the long molecule polyanthraquinone mentioned earlier. Upon discharging, the CO2 deatches from the polyanthroquinone in a reaction called oxidation.

Once that CO2 is released, the device can capture a new CO2 molecule on the next cycle. Even better, the battery discharge step could provide some of the original energy required for the charging process. This reduces the energy consumption of the charge/discharge process. When two of these cells were linked together to perform reduction and oxidation simultaneously, it reduced the wait-time required between cycles. As the oxidation cell discharges, the exhaust stream containing CO2 can be fed to the reduction cell for CO2 absorption.

The pure CO2 released can also be used to supply other industries. Examples include a source for carbonating drinks or for farmers who add CO2 to their greenhouses to maximize crop growth. Alternatively, the CO2 can be stored using compression tanks or by burying the CO2 underground so it does not reach the atmosphere. This prevents the CO2 from ever reaching the atmosphere.

CO2 can be captured and used for fizzy drink production. Source: Pxhere

This carbon capturing battery is unique because it can switch between absorbing or releasing CO2. Other carbon capture methods require significant amounts of time, chemical processing, or energy to regenerate before they can absorb CO2 again. The device is highly scalable and can be designed in many shapes and sizes, only requiring a power supply.

The researchers found that this technology was quite durable, lasting over 7,000 cycles with less than 30% loss in capacity for absorbing CO2. The device effectively absorbed CO2 at concentrations as low as 0.8%, similar to levels expected for ventilation of confined living spaces such as space modules, submarines, and buildings.

The researchers conducted a preliminary financial analysis for their technology and concluded the device could be economically feasible for industries. Costs ranged from $50–$100 per ton CO2 depending on the feed concentrations of CO2 being fed in and the applications under consideration.

While there is a global drive to reduce fossil fuel combustion, they will continue to be combusted long into the future, whether that be by the chemical, pharmaceutical or transport industry. The efficiency in design and scalability of this carbon capture technology brings significant potential to support sustainable economies.