The history of animal life, including humans, began 540 million years ago in the Cambrian period. Because most Cambrian life didn’t have skeletons, paleontologists studying this period rely heavily on fossils that preserve organs and other soft internal body structures, called soft tissue, to learn about these ancient creatures. A team of researchers from Yunnan University and Oxford University recently discovered well-preserved animal fossils from a previously overlooked group of rocks in China, revealing new information about Cambrian life.

They found these fossils, named the Chengjiang Biota, in a distinct section of rock in China called the Yu’anshan Formation. The Yu’anshan Formation is made up of a type of rock usually formed at the bottom of the ocean, called mudstone, which is excellent at preserving the bodies of dead animals and plants.

Scientists have observed 2 types of mudstones within the Yu’anshan Formation: lighter-colored ones they referred to as the event mudstone beds, and darker ones they referred to as the background mudstone beds. Paleontologists in the past collected fossils from the Yu’anshan Formation, but most of these fossils were from the event mudstone beds. In addition, the few fossils paleontologists collected from the background mudstone beds were poorly preserved.

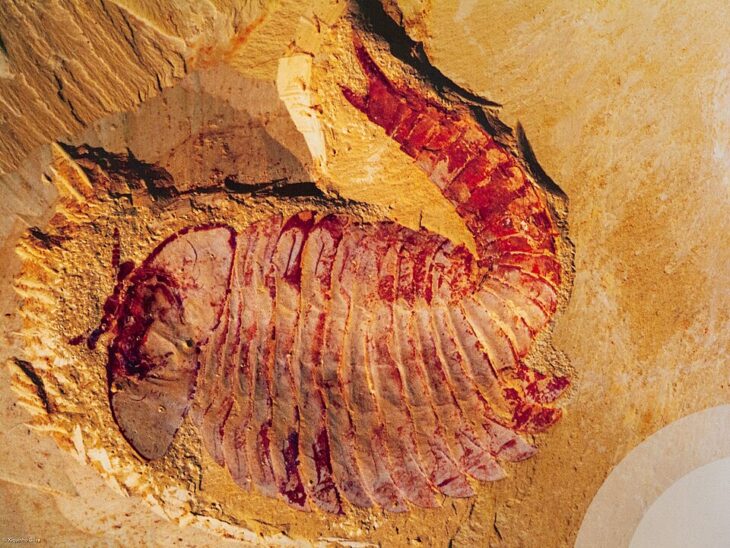

However, this research team found that the background mudstone beds preserved soft tissue even better than the event mudstone beds. They discovered fossilized musculature, eyes, nervous systems, and digestive tracts from dead animals in the background mudstone beds. They explained that soft parts like these are fragile and rarely preserved.

The researchers also discovered a new subset of deep-water animal fossils buried in the background mudstone beds. Scientists never found these animals in the past because the event mudstone beds primarily preserved shallow-water organisms. This team collected 1,328 fossils of 25 different species from the background mudstone beds between 2008 and 2018. They found that these fossils mainly came from bottom-feeders like sponges or anemones, known as benthos. The most common group of animals they found, called Euarthropoda, was related to spiders, crabs, and millipedes.

To study the fossils, the team took detailed, close-up images of the samples using a scanning electron microscope. Then they measured the chemistry of the fossils by blasting small areas with high-energy atomic particles and measuring the energy of the X-rays emitted in response, a method called energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy. They found that fossils from the background mudstone beds contained much more carbon than fossils from the event mudstone beds. They also found that the background mudstone beds were richer in iron than the event mudstone beds, but the fossils in the event mudstone beds were also iron-rich.

The researchers interpreted these chemical patterns to indicate that fossilization occurred differently in the background mudstone beds than in the event mudstone beds. They suggested fossils in the event mudstone beds formed when soft animal tissue was replaced with an iron-rich mineral called pyrite, via a process referred to as pyritization. Pyritization takes up iron from the surrounding rock, which could explain why the event mudstone beds were iron-poor while the fossils were iron-rich.

In contrast, they suggested that fossils in the background mudstone beds formed when soft tissue was converted into a thin layer of carbon, leaving behind a silhouette of the organism in the rock. This process, referred to as carbonization, doesn’t take up iron, so it leaves the rocks iron-rich.

The researchers proposed that differences in preservation between the 2 types of mudstone beds can reveal facts about the environments in which the organisms died. Pyritization suggests that animals in the event mudstone beds died in shallow, oxygen-rich water and were later washed into deeper water. However, animals in the background mudstone beds lived and died in deep water, and their preservation reflected their lifestyle. For example, some of these animals were picked at by scavengers and split apart, while others were rapidly buried and fully preserved.

The researchers concluded that their new fossil discovery has enabled the most complete account of the Chengjiang Biota thus far. In addition, the fossils provided new information about the bodies of ancient organisms and their habitats. They suggested these insights should help paleontologists better understand how Cambrian animals lived and how they evolved into the animals of today.