Cement is one of those building materials that you can find just about anywhere. When the cement starts to get cracked, fixing it is generally an easy task that involves widening the crack slightly before filling it with more cement. Now, imagine having to fix cracking cement that is buried 1 kilometer (3281 feet) underground! This is an issue that carbon storage researchers are trying to overcome.

Carbon storage is the process by which carbon dioxide gas is pulled from the air and put into sealed underground wells that will hold the carbon dioxide for the foreseeable future. It is being considered as a way to help reduce the impact of high carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Many different methods of fixing cracked cement in these deep underground wells are currently being investigated. However, the most innovative of these methods involves tiny organisms that can’t be seen by the naked eye.

In an effort to make these carbon storage wells safer and more effective for long term use, a team of scientists from the University of Montana decided to try a biological approach to fixing cracked storage wells. They wanted to know if the mineral (rock-like) material made by a specific type of bacteria (S. pasteurii) would be enough to stop carbon dioxide from leaking out of cracks in the wells. Furthermore, they wanted to find out the best way to grow the microbes so that the mineral material they make would create the strongest possible seal against the leaks..

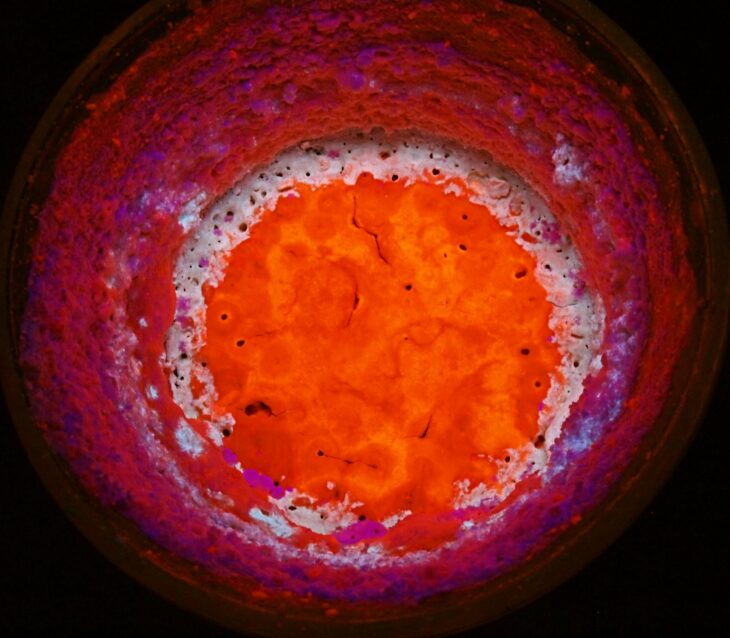

To do this, the researchers put a cement cylinder with a pre-made crack running down the middle into a container with two hoses. One hose was attached at the top of the container, and the other was plugged into the bottom. These hoses would allow for fluid to flow down through the crack in the cylinder and out of the container. Next, the researchers injected three fluids into the container in a specific order. These fluids would be used to establish the seal that would close off the crack and stop leaking fluids from escaping. The first fluid contained the bacteria, and the second fluid contained the nutrients needed for the bacteria to grow. The last to be injected was a fluid rich in calcium. This calcium-rich fluid was especially important, because it provided the building blocks for the mineral called calcite that the microbes would produce to fix the crack in the cement cylinder. The researchers ran a few different experiments using different fluid flow speeds and amounts of nutrients and calcium to see which combination worked best. They monitored how well the crack was being sealed by periodically scanning the fracture using X-rays, the way that a doctor scans a broken bone.

They discovered that the bacteria grew better and made a more complete seal of the crack when the flow rates of the injected fluids were fast. Injecting more of the nutrient fluid also helped the bacteria to grow better, resulting in more calcite build-up, leading to an improved seal.

Refining this “biocement” method of sealing cracks in deep well cement would allow for a faster, safer and more effective fix. Such a method is desperately needed, as cracks in either natural gas and carbon-storage wells could leak harmful materials into underground freshwater sources. If these calcite-forming microbes live up to what researchers expect of them, they may be glue that will hold carbon storage wells together far into the future.