Since the invention of the microscope and discovery of microbes, their role in everyday life has been, to say the least, contentious. As many of us have learned at one time or another, microbes can be a source of nasty diseases. At the same time, they are inevitably a part of us and our world. With the advent of sophisticated technologies that have peered deeper into microbial genetics and physiology, we’re now faced with a very interesting question: do we control the microbes or do they control us?

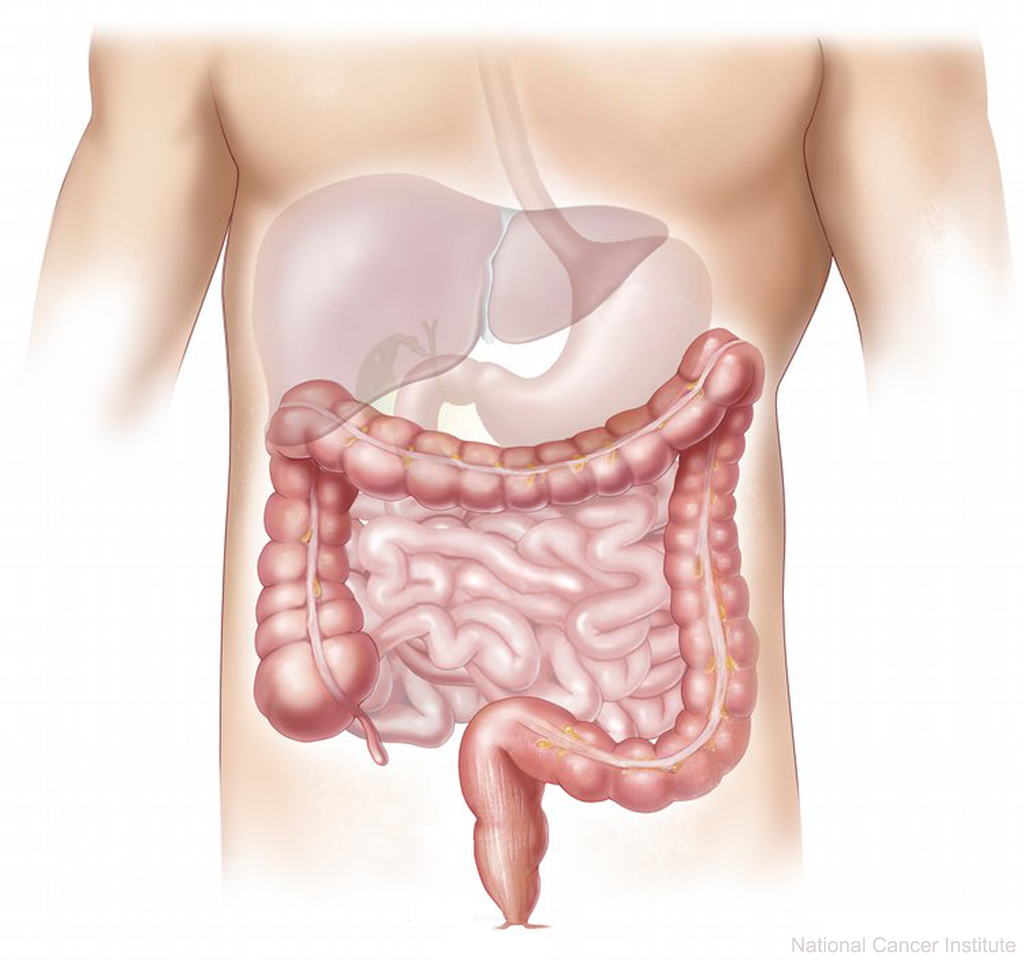

Much research has been done in the past decade that has uncovered unique relationships between us and bacteria. A study conducted collaboratively by scientists at Yale, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and University of Copenhagen investigated how bacteria living in our intestines interact with the human body, and how that may be a key factor in nutrition related illness such as metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of symptom associated with obesity that increase the risk of developing heart disease, diabetes, or stroke.

To test this, the researchers created three conditions in rats so they could compare differences in the bacteria and the chemicals they release between a normal diet, a short term high fat diet, and a long-term high fat diet. Right away, the long term high fat diet rats became obese and developed symptoms of metabolic syndrome compared with the other groups.

After looking at the physiology of the rats, the researchers saw changes in some key chemicals called short chain fatty acids. These fatty acids are important byproducts of digestion and they’re used in a variety of processes in the body, like energy, growth, and cell-to-cell communication. Through the process of elimination, it was discovered that one of those fatty acids, acetate, was significantly higher in the intestines of rats fed the long-term high fat diet. Acetate is a very common molecule in biology and you may have heard of it it’s common acetic acid form in vinegar. The acetate increase was solely due to the gut bacteria releasing it as a waste product into the intestine, where it was absorbed into the rat’s bloodstream.

To confirm this observation, the researchers used a variety of tools from antibiotics to actual surgical removal of the segment of the intestine housing those bacteria to ensure that the observation was indeed due to the microbes and not something else. Not only were the bacteria making more acetate, but the whole bacterial community changed. A group of bacteria known as Firmicutes increased in number and Bacteroidetes decreased in number. Firmicutes thrived on the extra fatty acid intake, out-competed the other species in the community, and pumped out more acetate as a result.

The acetate also influenced the physiology of the rat’s body. It crossed the blood-brain-barrier and triggered the release of fat storage hormones. One of those hormones, ghrelin, has significant control over appetite and energy use. This increase in ghrelin causes a significant shift in how it processes the nutrients coming in. Naturally, the scientists decided to see if they could do this without changing the diet of the animals. A group of rats were fed a normal diet with added acetate. Unsurprisingly, they saw the same thing happen as if the rats were on a long term high fat diet.

Does this mean we should figure out ways to decrease acetate in the body to fight obesity, diabetes and those other myriads of diseases? Not necessarily. This study merely demonstrated how complicated the interaction is between bacteria and host physiology. Acetate was the most obvious observation, but it could be part of a bigger combination of chemicals working with each other or on their own. We won’t know this without more research.

An important takeaway from this study, however, is that our bodies themselves are ecosystems. Commensal bacteria clearly play a role in that ecosystem, but to what extent? The idea that microbes are an important and normal part of our health is still very new to us. The research community has a great deal left to learn about how illnesses like obesity and diabetes develop, and what truly constitutes well-balanced nutrition. With all the new health information we constantly get and health choices we make day to day, it is just one slice of the pie.