Scientists first discovered planets outside our solar system, termed exoplanets, in the 1990s. Since then, scientists have found some strange systems. From the first recorded exoplanets orbiting a neutron star to systems where Jupiter-sized exoplanets orbit their host star 20 times closer than Earth orbits the Sun, astronomers keep finding distant planetary systems that look very different from ours. One type of exoplanet relatively easy for astronomers to spot is gas giants that are more than 2 times the mass of Jupiter, or more than 600 times the mass of Earth, referred to as Super Jupiters.

Astronomers have proposed 2 hypotheses for how some exoplanets get this big. The first is that they form this size or bigger out of a star’s initial surrounding gas and dust, called its protoplanetary disk. The second is that they result from collisions between 2 or more smaller gas giant planets. Scientists acknowledge that these hypotheses are not mutually exclusive, so some Super Jupiters could start that size and others could form by collisions.

However, scientists have also shown that the larger the Super Jupiter, the more elongated or eccentric its orbit tends to be, so any formation mechanisms must also explain this observation. They all agree that the answer lies in how planets interact. Collision proponents point out that the hypothetical collisions could warp Super Jupiters’ orbits. Proponents of high initial mass say that the gravitational pull from neighboring planets could also distort Super Jupiters’ orbits.

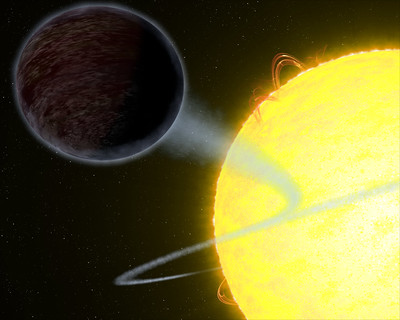

One team of astronomers recently tested these hypotheses on exoplanet TOI-2145b and its host star TOI-2145. This exoplanet has a mass of about 6 times that of Jupiter and more than 1800 times that of the Earth. They used precise and detailed data collected by previous researchers from multiple sources. These included observations of the exoplanet’s orbital period, width, and distance from the star from the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite or TESS, and its mass and orbital eccentricity from the Keck Observatory’s High Resolution Echelle Spectrometer or HIRES. This team collected their own data using the WIYN Telescope to bolster the previously existing HIRES data. They then combined all their information to create a complete picture of the stellar, orbital, and planetary characteristics of this system.

They found that the TOI-2145 star is approximately 1.7 times the mass of the Sun and a little more than 1.5 billion years old. Its exoplanet orbits at just over 1/10th the distance the Earth orbits the Sun, making a full revolution in about 10 days, and it has a highly warped orbit with an eccentricity of 0.2. For reference, Venus’s orbit, which is nearly a perfect circle, has an eccentricity of 0.007. Additionally, the orbit of TOI-2145b is nearly aligned with its host star, with an axial tilt of only around 7°. For reference, Earth has an axial tilt of 23.5°, which causes our seasons. They also found that the system has no other currently measurable exoplanets or nearby stars that might disrupt TOI-2145b’s orbit.

The astronomers’ next step was to see if they could recreate Super Jupiters with similar properties to TOI-2145b using mathematical simulations. They used the collisional dynamics code REBOUND to model how a planetary system with a specific-sized protoplanetary disk and 4 starting planets changed over 10 million years. They varied several parameters in the simulations, including the total mass of the 4 planets, how the mass was distributed between the planets, how far away they were from each other, and the mass of the disk. They compared the results of several dozen simulations with measurements of existing Super Jupiters from the Gaia Archive to see if they could replicate general trends in Super Jupiter systems.

To test the Super Jupiter origin hypotheses, the astronomers used simulations with relatively low protoplanetary disk mass to represent systems that grew via collision, and simulations with relatively high protoplanetary disk mass to represent systems where Super Jupiters started massive. They found that their simulated Super Jupiters were consistently similar to TOI-2145b’s in terms of the size and eccentricity of their orbits, regardless of whether the protoplanetary disk mass was high or low. However, their low disk mass collisional simulations reproduced the trend of higher-mass planets having more eccentric orbits, while their initially high disk mass simulations did not.

The team concluded that Super Jupiters more likely originated from collisions between planets. However, they acknowledged that it is certainly still possible for some exoplanets to simply start their lives several times bigger than Jupiter.