Fungi are everywhere. They live in our backyard topsoil, on trees in the forest, and sometimes on an old piece of bread in the fridge. We bake with fungi (yeast) and use certain species to ferment our beverages. Fungi are extremely important in the environment, as they break down and recycle tough carbon compounds like tree bark and leaf litter for energy. Fungi are also capable of recycling elements, such as manganese (Mn) and selenium (Se). While both of these elements are important elements in the environment at low levels, if concentrations reach too high, they can become harmful pollutants.

Certain species of fungi can make brown manganese oxide minerals out of Mn dissolved in water. These same fungi can also take Se dissolved in water and make incredibly small (nanometer-sized) solid red particles of pure selenium. Manganese oxide minerals and the solid red selenium particles do not dissolve well in water. Since dissolved forms of these elements are more toxic to aquatic life than their solid forms, scientists and engineers hope to one day use these fungi to clean up polluted environments.

Researchers from the University of Minnesota, Washington & Lee University, and University of Maryland wanted to know if some species of common soil fungi would be able to transform both Mn and Se simultaneously. If the fungi could manipulate both elements at once, this would be important for understanding how these potential pollutants are cycled through the environment.

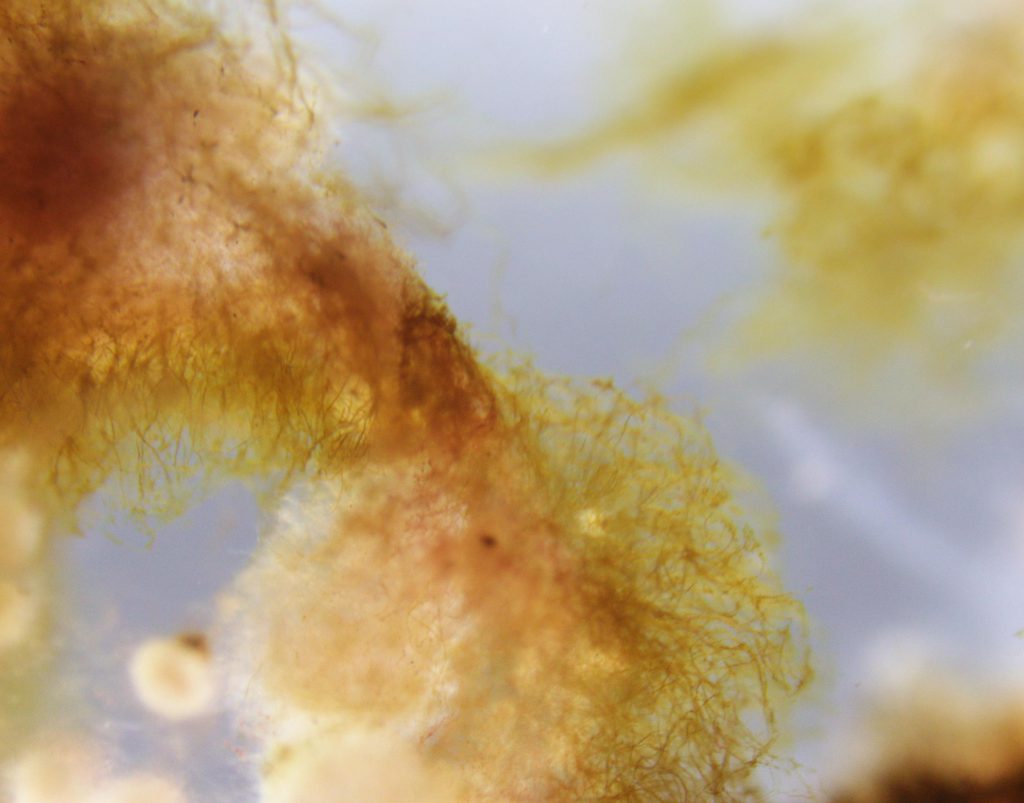

The common soil fungus, Paraconiothyrium sporulosum, makes brown Mn oxide minerals and red Se particles simultaneously. This photo shows the reaction happening in a flask. Credit: Mary Sabuda

To answer their question, the researchers grew the two species of fungi, Stagonospora sp. and Paraconiothyrium sporulosum, separately in flasks with water and various nutrients. They then added both dissolved Mn and dissolved Se in concentrations similar to contaminated soils and waters (~17 mg/L). For comparison, they also grew both fungi with Se only. After 14 and 31 days of growth, they measured how much Mn and Se were removed from solution by the fungi using techniques called inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry, which uses heat to vaporize elements and light to determine their amounts, and ion chromatography, which uses a special column to separate compounds in water by their size. They also used a technique called x-ray absorption spectroscopy to detect Mn oxide structures and any forms of Se associated with the fungi. Finally, the researchers also looked at the fungi under a high-powered electron microscope to visualize any Mn or Se minerals.

It turns out, the fungi can remove Mn and Se from solution simultaneously to form solids. Under the microscope, they found Mn oxide minerals and solid Se particles side-by-side. They also found that in some cases, the Mn oxide minerals could recycle Se back to its dissolved forms. This is exciting, since it appears there is a cryptic or ‘hidden’ part to the Se cycle in nature that was not previously known. With this new information, scientists can better understand and predict global Mn and Se cycling and use this knowledge to design better strategies for cleaning up polluted environments.