Cancer of the ovaries, or ovarian cancer, can go undetected until it spreads to other parts of the body, like the pelvis and stomach. Once the cancer has spread, chances of survival are much lower, because it is more difficult for doctors to target.

The spread of cancer from its initial site to somewhere new in the body is called metastasis. Researchers hope to discover which genes or proteins are responsible for metastasis to identify molecules that can be targeted to treat it.

When ovarian cancer spreads to the intestines, it is called ovarian cancer bowel metastasis. Scientists previously identified several genes involved in bowel metastasis, but don’t yet understand their roles. Scientists in that study examined a gene encoding for a protein located on cell membranes. The protein is abundant in bowel metastasis, and plays a role in abdominal metastasis and growth.

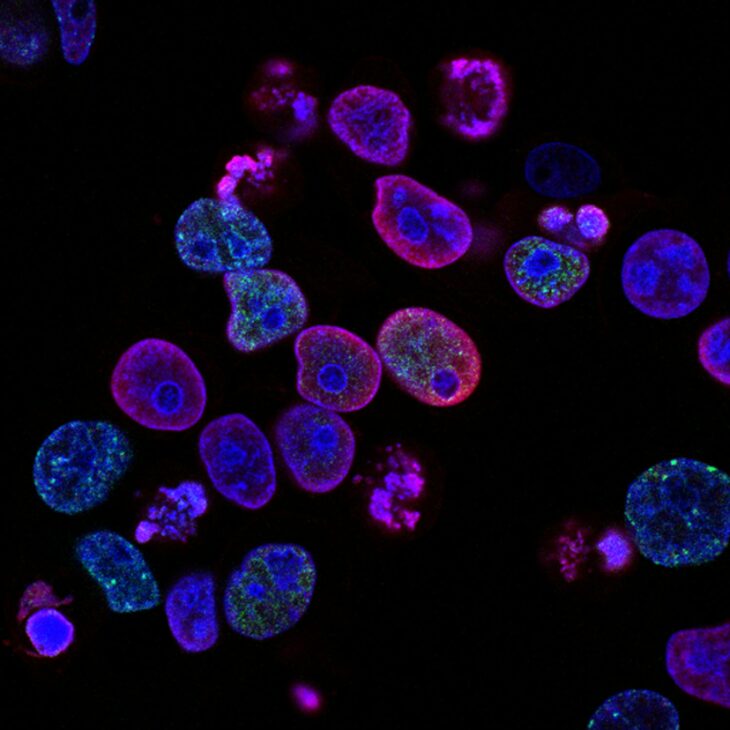

In this new study, scientists measured the effect of the membrane protein on ovarian cancer cells. To do so, they put the cancer cells on a testing plate with a gel for the cells to grow on. The scientists labeled the cancer cells with a fluorescent dye and mixed them on the plate with healthy cells and the protein.

Using a special imaging software, they could distinguish the cancer cells from healthy cells because the cancer cells lit up. After a few days, the scientists examined the cells to see if they survived and multiplied. From this experiment, the scientists learned the membrane protein made the cancer cells live longer.

They also observed this protein made the cells stickier, which would help cancerous cells leaving the original tumor stick to a new organ and form a metastasis. Because the protein is sticky, the scientists also inferred it would allow more cells to spread to other areas of the body, like the pelvis and stomach.

The scientists chose a drug that would stop cell division and slow the spread of metastasis. However, this drug is toxic to healthy cells. To target the membrane protein found on cancer cells, the scientists used a therapy drug that contains a molecule from the immune system called an antibody. The antibody is good at binding to the membrane protein, so it ensured the drug would get to the tumor cells and not the healthy cells.

They tested the drug on mice, first by using established human cancer cells. These cells are more adapted to lab settings than cells in our bodies are. The mice given established cancer cells were used for 2 experiments. One experiment tested how well the drug prevented metastasis in the mice. In this experiment, the scientists gave 21 mice the drug treatment 3 days before injecting them with cancer cells, and continued treatment for 2 weeks after.

The other experiment tested how well the drug worked after the mice already had cancer cells. In this experiment, the team injected 15 mice with the human cancer cells, and gave them the drug starting 1 week later, for a total of 4 weeks. They dissected both groups of mice after the experiments to weigh and count their tumors. The scientists found the drug decreased the number and weight of tumors in both sets of mice.

Next, the scientists used cells taken directly from ovarian cancer patients. They injected the tumor cells into mice, in another 2 sets of experiments. One was a “pre-treatment” experiment, where they gave the mice the drug 3 days before injecting them with tumor cells. Afterwards, they gave the mice 5 more treatments at an interval of 4 days.

The other was a “therapeutic” experiment, where the team gave the mice the drug 2 weeks after the tumor injections. They gave these mice a total of 6 treatments, at an interval of 4 days. They measured all tumors in both experiments weekly using ultrasounds. In these experiments, they found the drug only worked to prevent tumor formation, but it didn’t shrink or slow the growth of tumors that were already present.

The scientists hypothesized that waiting to begin drug treatment until 2 weeks after injecting cancer cells was too long. They suspected the tumor cells began to “stick” after only a day or two. Since they showed the drug works to prevent cells from sticking, giving the drug to mice after that 1-2 day window wouldn’t prevent the cells from adhering and therefore wouldn’t prevent metastasis.

The team concluded this drug works in mice as a possible preventative treatment for metastasis, but further work is necessary before it could be used in humans. They also suggested future work should focus on treating the mice within 2 days after the injection, to see if this prevents cells from adhering to other organs and forming metastasis.