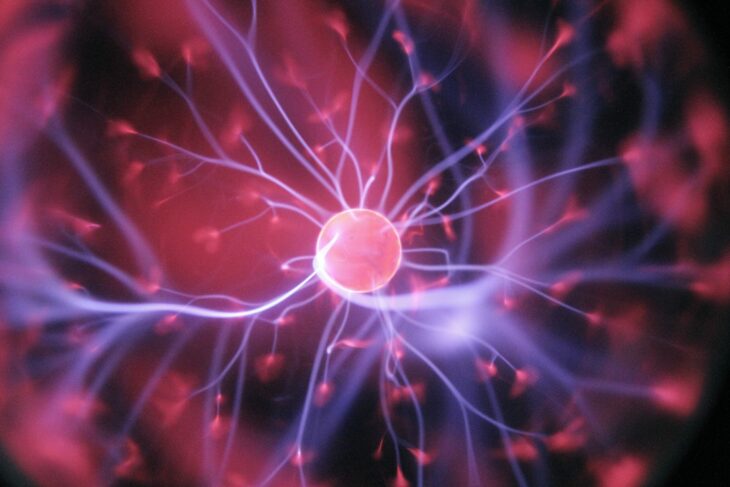

The nerve cells, or neurons, in our bodies stretch from the brain and spinal cord all the way to the tips of our fingers. They form connections with each other that deliver signals throughout the body, like electrical wires in a laptop.

Neuronal “wires” are wrapped in a protective fatty layer called the myelin sheath. Without this layer, the signals might not be transmitted quickly enough or delivered successfully to another neuron. Impaired nerve signals can cause problems like blurred vision, loss of balance, or mood swings.

A component of the myelin sheath enabling it to successfully insulate the neuron wires is called the myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein, or MOG for short. MOG is important for protecting the neuronal signals across the central nervous system, which includes the brain, spinal cord, and eyes.

Our body has an immune system that protects us from getting infected by external organisms like viruses, fungi, or bacteria. When a healthy immune system fights off these organisms, it creates a protein called an antibody. Sometimes the immune system malfunctions and turns its defenses towards its own body. When the immune system starts attacking its own healthy cells, this can lead to an autoimmune disease. The antibodies that attack healthy cells are called autoantibodies.

A similar type of autoimmune attack can occur with MOG, as well. MOG antibody-associated disorder, or MOGAD, is a disease where a patient’s antibodies start attacking their own MOG proteins. Patients with MOGAD experience failure in nerve protection in their central nervous system, as this attack destroys the myelin and “unwraps” the neurons. This can cause symptoms like swelling in the eyes and spinal cord, temporary vision loss, or sharp pain across the body.

MOG was previously not thought to be involved in the peripheral nervous system, which includes nerves in other parts of the body, like the arms and legs. Therefore, patients who showed symptoms in their peripheral nervous system were not diagnosed with MOGAD or other MOG-related diseases. However, scientists recently described a possible connection between MOG and symptoms in parts of the body controlled by the peripheral nervous system, including the limbs, chest, and shoulders.

A team of researchers from the UK and Australia therefore wanted to test whether MOGAD was associated with the peripheral nervous system. They performed a detailed clinical and immunological characterization of blood samples from patients with MOGAD from a large Australasian cohort of 4,820 adults.

The researchers carefully selected 19 people from the cohort who were diagnosed with MOGAD and had experienced problems with their peripheral nervous system. Their symptoms included limb pain, sensory abnormalities, and involuntary twitching of limbs. The researchers confirmed these symptoms were not due to other diseases in these patients.

The team first tested if the patients’ peripheral nervous system symptoms responded to treatments like steroids or extra antibodies generally used to treat MOGAD. The researchers gave the treatments to 15 eligible patients. They found 3 of these patients showed complete resolution of their peripheral nervous system symptoms and 9 of the patients showed partial resolution.

If their peripheral nervous system symptoms were alleviated by MOGAD treatments, the researchers concluded these symptoms were possibly related to MOGAD. Some patients even reported their symptoms recurred when they reduced the amount of MOGAD treatments they were taking.

The researchers identified another possible explanation for the patients showing symptoms in both their central and peripheral nervous systems. They found 4 of these patients had antibodies that bind to MOG as well as two similar proteins that insulate nerves in the peripheral nervous system. It is rare but possible for someone to have two different types of autoantibodies like this, which leads to syndromes in both the central and peripheral nervous systems.

The researchers found overlap between MOGAD and the peripheral nervous system, but their results were too limited to be definitive. Previously, MOGAD was only associated with syndromes of the central nervous system, which could lead to late-stage diagnosis of the disease and less effective treatment. They suggested recognizing a link between MOGAD and peripheral nervous system symptoms could help clinicians diagnose it in patients at an earlier stage. They concluded further research is needed to determine if some patients are also experiencing a secondary autoimmune disease related to these symptoms.