There are many dangerous diseases and viruses in the world, some more common than others. One common virus is the Epstein-Barr virus, or EBV for short. It is a leading cause of a disease called mononucleosis, which is better known as mono. EBV is so common that 90% of Americans become infected with EBV by the time they are 35. EBV affects the cells that line the surface of the throat, allowing the virus to spread via saliva. It also infects white blood cells related to the body’s immune system.

Previous researchers have noticed a potential link between EBV and the disease known as Multiple Sclerosis, or MS. MS is an autoimmune disease that attacks the central nervous system and can damage the brain and spinal cord. MS is a rare disease, whereas EBV is extremely common. Some people develop MS after contracting EBV, but the link between MS and EBV is currently unknown.

A group of scientists from Stanford University recently conducted a study to determine if EBV was connected to MS. They wanted to determine any similarities shared between molecules found in the EBV virus particles and molecules found in tissue samples from people with MS. Similarities in the structure and function of molecules are called molecular mimicry. These scientists were specifically looking for molecular mimicry between proteins found in the nucleus of the EBV virus, called EBNA1, and proteins found in the central nervous system, called GlialCAM.

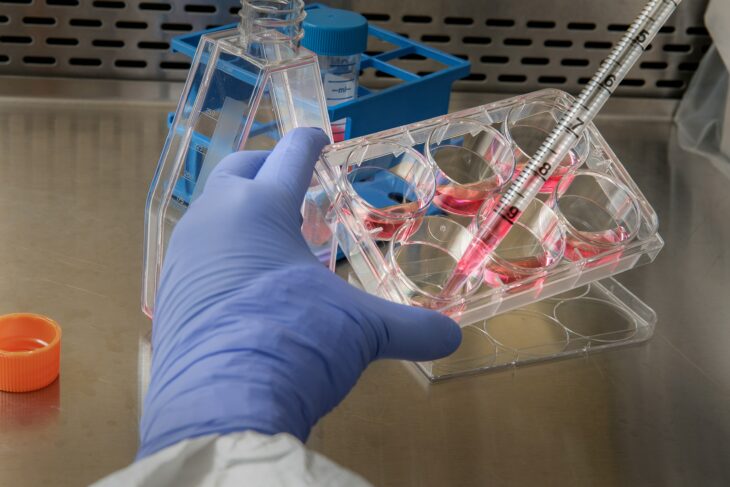

The scientists collected spinal fluid and blood samples from 36 MS patients and 20 unaffected individuals. They observed differences in cells related to the body’s immune system from both the blood and spinal fluid samples. First, they sorted a type of white blood cells that make antibodies, called B cells, using technology that rapidly analyzes single cells or particles as they flow past lasers. Then, they looked at the differences in B cells from the blood samples and spinal fluid.

They compared the number of antibody-producing stem cells, called plasmablasts, in both the spinal fluid and blood samples. More plasmablasts were found in the spinal fluid then the blood samples. When they looked more carefully at these different plasmablasts they discovered molecular mimicry between their EBNA1 and GlialCAM proteins.

The scientists found that in people with MS, the viral protein EBNA1 helps EBV persist in the body for life. It essentially stops the immune cells from recognizing the presence of EBV and therefore stops the immune system from fighting off the virus. The nervous system protein GlialCAM is so similar to this viral protein that antibodies for the virus recognize it and bind to it instead of to the virus.

They also found that molecular mimicry of EBNA1 in GlialCAM is more reactive in patients with MS. MS destroys a layer made of protein and fat that forms around nerves, called myelin. This process, called demyelination, causes nerve impulses to slow down or stop. Molecular mimicry was especially prevalent in a subset of patients with MS that also had a higher rate of damage to their myelin. The scientists suggested that molecular mimicry could explain how EBV also damages myelin.

The scientists suggested future studies should focus on understanding the mechanistic link between EBV infection and the pathology of MS. A clearer understanding of how EBNA1 and GlialCam are connected could help scientists determine how demyelination occurs. This breakthrough could help doctors develop medications to slow the progress of MS.