Earth’s Moon is perhaps the most obvious single feature in the night sky. And scientists largely agree on how it came to be: in the early days of the Earth’s formation, a smaller planet-sized object slammed into it, throwing loose a clump of material that was big enough to gravitationally pull itself into a sphere and moving slowly enough to remain bound by Earth’s orbit. But, while the giant impact hypothesis answers the question “Where did our Moon come from?,” it is still an open area of debate for other moons in the solar system, including Mars’ moons Phobos and Deimos.

One competing scenario for the origin of these moons is that 2 small objects came flying towards Mars early in its existence and collided with a surrounding cloud of gas and dust left over from when it formed. This dust cloud slowed them down enough that Mars’ gravitational field captured them. This is known as the gas-drag capture hypothesis, and while it may explain why Phobos and Deimos are made of different materials than Mars, it has other problems to address.

One problem is that to slow down an approaching object enough for it to be captured, the dust around Mars would have needed to be several times denser than current models of solar system formation would suggest. Another problem is simple probability. Both Phobos and Deimos’ orbits are within 2° of Mars’ equator, but there’s only about a 0.00001% chance that 2 objects on any trajectory would both head towards Mars at angles aligning with its equator.

To test whether this scenario was possible, 2 scientists from Japan created a model to calculate the trajectories of Phobos-sized objects hurling towards Mars. They aimed to demonstrate that these problems do not render the gas-drag capture hypothesis as implausible as scientists previously thought.

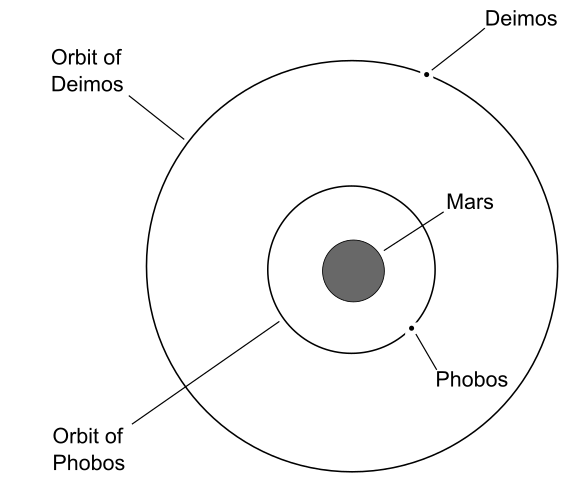

Phobos orbits Mars around 3,700 miles or 6,000 kilometers above Mars’ surface and is slowly falling towards it. Deimos orbits 14,600 miles or 23,500 kilometers from Mars. “Mars moons” by Muskid is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

To begin, they identified the relevant equations of motion that their model would need to incorporate. These equations relate several properties of an object approaching Mars, including its angular velocity, its distance from Mars, its potential energy, and the drag force slowing it down. They also included the mass of Mars and the conditions of the material surrounding it in the past, which they referred to as its primordial atmosphere. They assumed this atmosphere would have a temperature of 200 Kelvin, which is approximately -73°C or -100°F. They assumed its density would be 4.7 × 10-7 kilograms per cubic meter near Mars’ surface, decreasing exponentially with height.

Then the team needed to input the initial trajectories for the incoming moons. They tried 8 different possible speeds. These ranged from 20 to 160 meters per second, corresponding to approximately 45 to 360 miles per hour, with increments of 20 meters per second or 45 miles per hour. The moons also had 4,096 possible incoming angles relative to Mars’ equator and poles. Thus, the team tested a total of 32,768 combinations of initial courses for moons hurtling towards Mars.

Based on their models, the researchers found that objects passing through Mars’ primordial atmosphere had 3 potential fates. Depending on their speed, they either escaped Mars’ gravitational field, were temporarily captured, or were permanently captured. Nearly 100% of objects moving at the lowest speed were captured, whether temporarily or permanently, while only 10% of objects moving at the fastest speed were captured. In total, the team estimated that about 1 in 50 objects that come hurtling towards Mars gets permanently captured. And in cases where these objects lost enough energy for Mars to capture them permanently, their orbits were constrained to within 10° from Mars’ equator, particularly those with low initial speed.

Based on these results, the team proposed a possible history for Mars’ moons, Phobos and Deimos. Based on their chemical composition, these moons formed somewhere in the outer solar system, in or beyond the asteroid belt. Sometime later, they were scattered out of their original homes by Jupiter’s gravity. After that, they fell towards Mars too slowly to escape and at the right angle to be slowed down by surrounding gases, where they were permanently captured in eccentric orbits. Over time, their orbits slowed, became more circular, and shrank towards Mars.

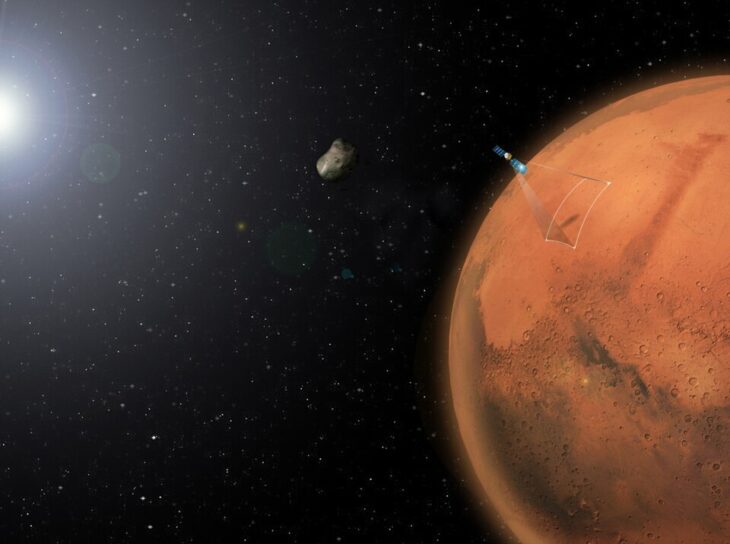

The team’s proposed scenario aligns well with what astronomers observe in Phobos and Deimos today, leading the team to conclude that they had likely been captured. The future Martian Moons eXploration mission will provide more information about the origins of these moons by orbiting Mars, then Phobos for detailed observation and remote sensing, and collecting a sample from its surface to return to Earth. The mission is currently scheduled to launch in 2026, and the Phobos sample is expected to return to Earth in 2031.