The last two years have made it difficult to imagine our lives without masks and sanitizers, all thanks to a virus. The SARS outbreak of 2003 across Asia introduced the world to coronaviruses. SARS-Cov2 is also a coronavirus but it’s more transmissible and thus spreads faster. Billions of people have been infected by it and millions have succumbed to it across the globe. Measures to prevent COVID-19 disease progression from mild to severe cases include vaccination, monitoring of symptoms, containment and treatment with antivirals. In those instances where vaccination is refused or is ineffective, the role of antiviral medications becomes critical.

A non-toxic, effective antiviral, if given to patients early in infection, could help to control the viral load, prevent severe progression of symptoms, and limit transmission. During infection, the coronavirus blocks molecules that would otherwise activate genes to establish an antiviral state within the cell. As a result, the cell is unable to fight back, allowing the virus to multiply freely. A good antiviral drug should be able to prevent the virus from doing this, minimizing the spread of infection. An Australian research group decided to investigate a potential candidate drug called ivermectin.

Ivermectin is an FDA-approved drug for diseases caused by certain intestinal worms and malarial parasites. But in the last decade, ivermectin has been shown to inhibit HIV-1 multiplication. It has also been demonstrated to limit infection by viruses that, like the SARS-Cov2 virus, have RNA as their genetic material. What’s promising is that the mechanism that ivermectin blocks is the one that the 2003 SARS coronavirus uses for infection. Taken together, these experimental reports suggested that Ivermectin may be an effective drug against the SARS-Cov2 virus.

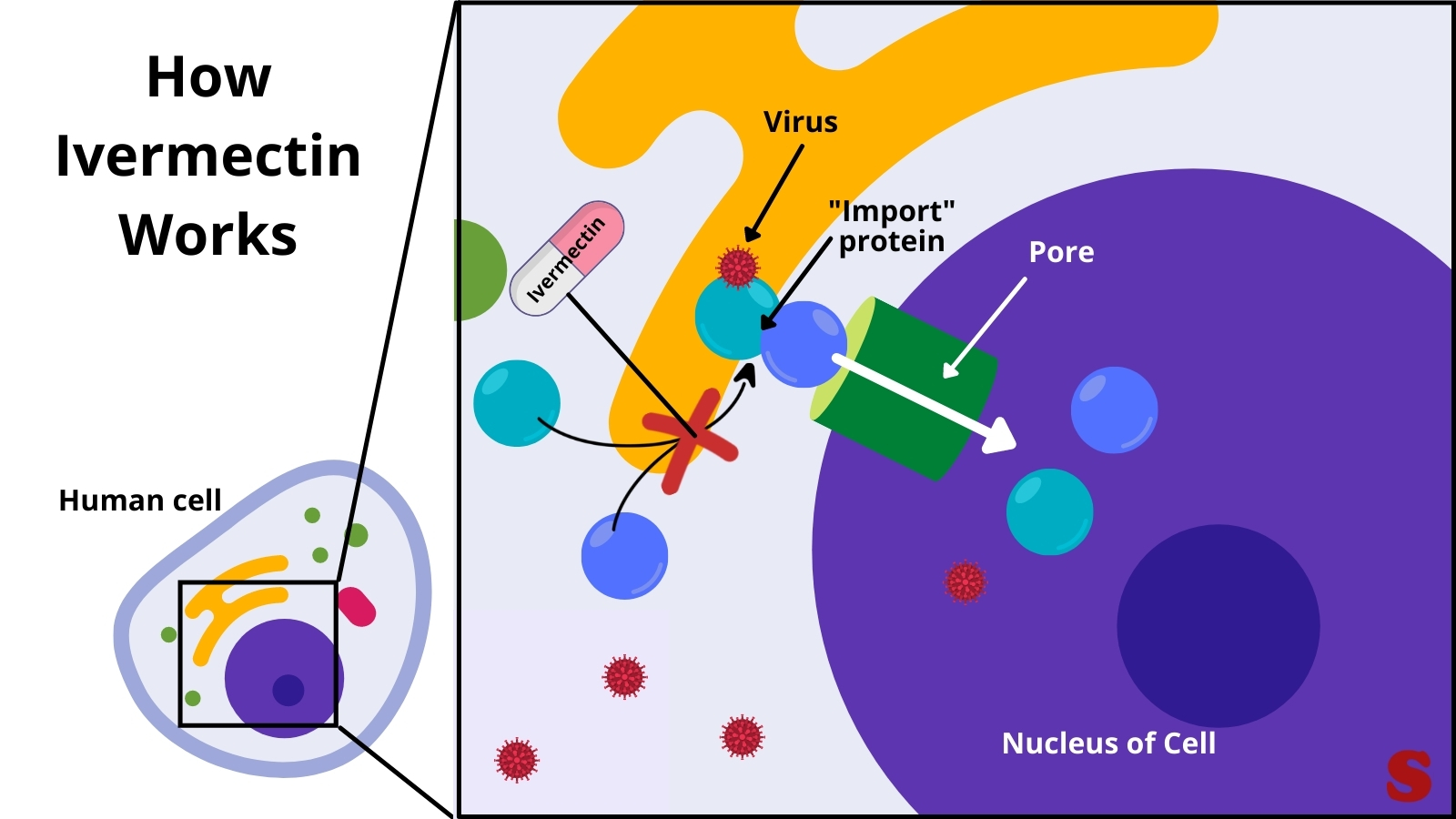

After the virus has already infected the cell, ivermectin appears to block the formation of molecule that the virus otherwise hitches a ride onto and gets into the cell nucleus to shut off it’s natural anti-viral system. Image by Gina Misra (Sciworthy) and information from here. Click image to enlarge.

A group of researchers from the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity and Monash University in Australia set out to test the antiviral activity of ivermectin toward SARS-Cov2. Using a technique called cell culture, they infected human cells with samples of SARS-CoV2 taken from real patients, and then treated the cells with ivermectin. Then, they harvested the cells as well as the surrounding medium to see if the SARS-Cov2 virus replicated.

To detect the virus, the scientists needed to detect if its RNA is present in both the cells and in the surrounding medium. They employed a test called RT-PCR to measure the viral RNA content in both. They found that compared to control samples, treatment with ivermectin results in approximately 5000-fold reduction in viral RNA within 48 hours due to its inhibitory action. This implies that ivermectin treatment can lead to the loss of essentially all viral material within 48 hours of its administration. In addition, no further reduction in viral RNA was observed at 72 hours.

To test for the effectiveness of ivermectin, the researchers treated SARS-Cov2 infected cells with serial dilutions of ivermectin. A serial dilution is a set of solutions of the drug that decrease in concentration, usually by a factor of 10. It is standard practice if you’re trying to determine the optimal concentration to use. Just as before, they noted a 99.98% reduction in viral RNA at 48 hours in their samples. This further suggested that a single dose of Ivermectin can control viral replication within 24 to 48 hours in the human cell line.

Ivermectin is a unique candidate because it already has an established safety profile for human use and has FDA-approval for a number of parasitic infections. A high dosage of ivermectin has comparable safety to the standard low-dose treatment (using low doses of a drug across time intervals). However, there isn’t enough data on its safety profile for human use during pregnancy.

In the recent Phase III clinical trials of Ivermectin in dengue virus patients in Thailand, a single daily dosage of ivermectin was found to be safe but insufficient for any clinical benefit. This suggested that an improved dosage regimen, perhaps one with multiple additions should suffice. Although the dengue virus is very different from SARS-Cov2, the trial design can be used. The next step is to evaluate different dosing regimens according to what we already know about it’s safety in humans.

From these results, they confirmed the anti-viral activity of Ivermectin against the SARS-Cov2 virus. However, Ivermectin still remains as one among the many candidates. It is important that it is subjected to benchmark testing against other potential antivirals for SARS-Cov2. Nevertheless, ivermectin could be beneficial in a clinical setting and, as the researchers from the study propose, it should be pursued rapidly.