Dementia is a condition that many of us are all too familiar with within friends and family. Dementia itself is a blanket term that describes several conditions including a decline in thinking skills, memory loss, and altered behavior, feelings and relationships. In contrast, Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia and occurs in 10% of people over the age of 65(1). What makes this even more troubling is the proverbial “Silver Tsunami” which lays on the horizon. The “Silver Tsunami” refers to the ever-growing swell of adults over 55 in many developed countries as a result of improved life expectancy. Riding with this wave are the 82 million people worldwide which are expected to be diagnosed with dementia by 2030 and 152 million by 2050.

With the wave of dementia cases at hand, research on preventative measures is now more important than ever. This holds especially true for preventative measures for individuals with a history of dementia or those beginning to experience subjective cognitive decline or SCD. SCD is the self-reported experience of worsening or more frequent confusion or memory loss. A report by The Lancet International Commission on Dementia Prevention and Care suggested that between one-third and one-half of all cases of Alzheimer’s disease are directly correlated to an individuals lifestyle earlier in life.

This spurred a recent 2020 study at the Centre for Research on Ageing, Health and Wellbeing (CRAHW) in Canberra, Australia which aimed to investigate how lifestyle changes of those in the early stages of dementia could curb the trajectory of the condition. The study consisted of an 8-week lifestyle modification program which attempted to reduce dementia risk for people experiencing cognitive decline. Participants were from Canberra, Australia, older than 65 and diagnosed with or reported SCD.

Over the 8-weeks, all study participants completed several online educational modules about dementia prevention. The educational modules taught participants about the known mental benefits of cognitive engagement, the Mediterranean diet, physical activity.

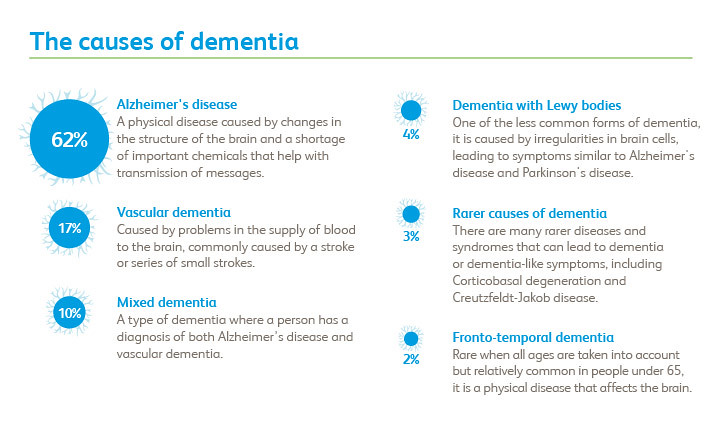

“Dementia – The causes of dementia” by UK Prime Minister is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Cognitive engagement includes a wide range of activities from “reminiscing with a person about the good ol’ days” to playing the piano and has long been acknowledged by doctors to combat advancing dementia. The idea of ‘use it or lose it’ has become very popular in the study of retaining brain function with age. The claim is that to maintain your cognitive ability, you must use your cognitive abilities.

Why the Mediterranean diet? They modeled their experiment after several previous studies. One of those studies had positive results from the diet in cardiovascular disease and another had positive results in patients with cognitive decline. If you haven’t heard of the Mediterranean diet, Mayo clinic describes it as mostly plant based foods with the inclusion of fish, poultry, beans and eggs, but little red meat. Physical activity was included in this study because they found in their background reading that it had not been studied enough in patients with cognitive decline.

One group of participants was used as a baseline where they engaged in nothing else except for the online program. The other group, the intervention group, completed the same online educational modules and took part in activities including meeting with a dietitian and exercise physiologist and completing brain training. These practical components were designed to assist the participants in actually implementing changes into their lifestyles.

After the 8-weeks of intervention, the scientists continued 6 months of follow-ups in which they conducted several tests of cognition including decision making, logic, and speech. Over these 6 months, the scientists found even though the members of this study were already experiencing the beginnings of cognitive decline, the short period of intervention significantly improved overall cognition scores. The baseline group showed improvement, but to a much lesser extent.

The crux of this study is the importance of professional support in helping individuals to fight dementia. Education alone did not significantly help the control group avoid decline. When this control group was presented with ways to curb cognitive decline on a silver platter, we don’t see the striking improvements in cognitive performance that we do in the intervention group. The difference is the inclusion of professionals in the prevention process. Dementia is not a battle to be fought alone. Although cognitive decline is not clearly preventable in all cases, taking advantage of professional support through dietitians, exercise physiologists, or structured brain training led to drastic change. Importantly, even patients already experiencing symptoms have the potential to improve. While the “Silver Tsunami” still appears daunting, tangible lifestyle changes may itself be the necessary life preserver for an aging population.